On the western edge of West Campus, nestled in the center of HillTop apartments, lies a small, two-story building made of wood and limestone. The building is the last remaining piece of Wheatville, Austin’s first community of formerly enslaved people.

The wooden house, also known as the Gold Dollar Building, now houses The Cauldron, a coffee shop and bar that opened last fall. In its 150-year-old history, the building housed a grocery store, newspaper, church, laundromat, ice cream store and barbeque restaurant in the center of Wheatville, a community of freedmen on the outskirts of early Austin. Wheatville stretched from 24th Street to 26th Street, with most residents living along San Gabriel Street and Longview Street. The Cauldron is now the last standing structure from the once bustling community.

Historical records of the community and its residents are hard to come by. In fact, a Google search of Wheatville will first show the Wheatsville Co-op, the Austin grocery store named after the community. Edmund Gordon, professor of African and African diaspora studies, said the lack of historical records is because the privilege to preserve history lies with those in political, economical and social power.

“Historical archives are created by people who are in a position to be able to create historical archives,” Gordon said. “The relatively poor and marginalized people of the community of Wheatville historically have been able to keep alive some memory of that community orally, but they weren’t in a position to make the paper that is the basis for the archives.”

History

Freedman James Wheat and his family established Wheatville in 1869, making it the first Black community associated with Austin after the Civil War. Gordon said the area north of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard was primarily inhabited by freedmen because it was on the outskirts of the city and not considered valuable at the time.

The first floor of the Gold Dollar Building was likely built by George Franklin, a Black carpenter, in 1869.

Freedman Jacob Fontaine and his family purchased the lot next door at 2400 San Gabriel St. in 1870. In 1876, Fontaine began publishing the Gold Dollar out of his home until it was burned down in 1879, said Tara Dudley, assistant professor of architecture. Despite the paper’s name and common misconceptions, Fontaine never owned the Gold Dollar Building.

According to the Texas State Historical Association, The Gold Dollar published stories about religion, education, racial justice and family ties. It’s uncertain when the paper ceased publication, but TSHA estimates it could have been in print until 1880.

Fontaine owned the lot next to the Gold Dollar building until he sold it in 1894, at which point he is listed as living there.

After UT opened to students in 1883, the city started expanding into areas traditionally owned and populated by Black residents through land acquisitions and gentrification. As the University expanded, sororities and fraternities moved into the area, Gordon said, driving the cost of living higher than previous residents could afford.

“The opening of the University in 1883, and then the population of the area expanding out from the University, (is what) I refer to as one of the first episodes of anti-Black gentrification in the city,” Gordon said.

The University did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

In 1928, the city of Austin developed a master plan to push the city’s Black residents out of their communities and into what is now known as East Austin in order to segregate the city. In order to draw all Black residents into one district, the city moved all Black schools, parks and other segregated facilities east of East Avenue, which is now the I-35 highway.

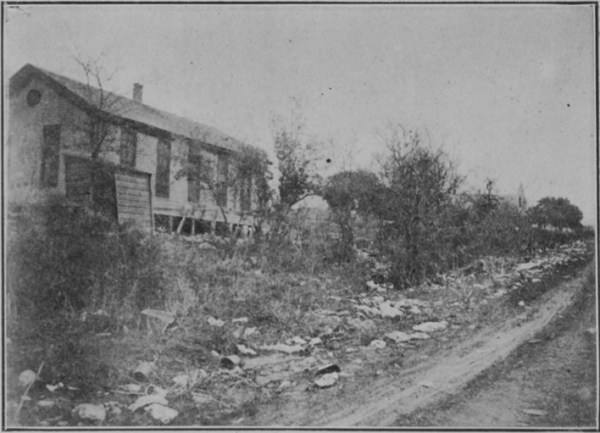

Dudley said the city excluded Wheatville from amenities like trash collection, electricity, paved streets and water. Combined with the influx of students, she said, Black residents began to leave.

One of the city’s two trash dumps was located in Wheatville, but city trash wagons did not collect Wheatville trash and often dumped garbage along the streets, according to a UT social survey in 1913.

“On one hand, you have residents moving out to be able to access the amenities that they were allowed in East Austin,” Dudley said. “On the other hand, there are buildings and people getting priced out by other structures that become more relevant.”

Amy Shreeve, a research assistant to the Campus Contextualization Initiative, created a map of Wheatville from 1880 to 1950 tracking the number and racial makeup of households in the area during her undergraduate research. Shreeve, who graduated in spring 2023, said her research shows a pattern of land dispossession.

“I lived in West Campus for three years and people only know Wheatville because of the Wheatsville Co-op, the grocery store,” Shreeve said. “That is on purpose. It’s not that all those people disappeared because they didn’t want to live in that area anymore, that land was taken from them and they were dispossessed through the expansion of the University.”

Implications

Gordon said the erasure of Wheatville illustrates a larger pattern of Black erasure throughout Austin’s history. In 1870, Black residents made up 36% of Austin’s population. In 2022, the U.S. Census Bureau estimates Black residents made up 7.7% of the population.

“Black folks in the city of Austin have always lived in its margins,” Gordon said. “As the city of Austin has expanded and as the value of lands has shifted, the racial patterns of habitation and use in Austin has shifted as well, with Black folks always losing out to the dominant community. As one area becomes an area of less value, it is inhabited by Black folks. As soon as it becomes more valuable for one reason or another, white folks move in, Black folks out.”

The same pattern of anti-Black gentrification can be seen in the development of East Austin today, Gordon said. Blackland, a historically Black neighborhood east of I-35 and between Manor Road and MLK Boulevard, is a prime example.

“Blackland … just in the 30 years I’ve been here has changed dramatically,” Gordon said. “That used to be a completely Black area.”

Shreeve said the erasure of Wheatville caused Black property owners to lose out on land that is now very valuable. Currently, Shreeve is working with UT lecturer Rich Heyman to document the amount of wealth Black landowners could have accrued if they were not forced out.

“It’s a lot of money that was lost, a lot of Black landowners and Black homeowners who got pushed out by no fault of their own,” Shreeve said. “They lost out on a significant amount of generational wealth.”

From 2012 to 2018, the Gold Dollar Building housed a restaurant called Freedmen’s BBQ. Dudley said the building’s current use as a coffee shop is a good way to both serve West Campus and keep the history of the building alive.

“We want buildings to retain use to continue to be the life of a community,” Dudley said. “I think it’s wonderful that the building is continuing to be used as long as the occupants and the owners understand that history and are willing to retain the historical aspects of the building.”

The Cauldron declined to comment on the building’s history.

Students should know the history of where they are to understand how they relate to their surroundings, Gordon said.

“I do think that there’s an issue in terms of memory, who gets remembered and who doesn’t,” Gordon said. “Black folks disappearing from Austin is related to that whole history.”

Originally published Oct. 3, 2023, in The Daily Texan

By Madeline Duncan

Photo by Lorianne Willett